Vicon motion analysis systems is known as the gold standard for analyzing human movement. However, many professional or collegiate teams just don’t have the resources to install such sophisticated technology into their own facilities. This means that they miss out on the valuable insights and biomechanical analysis these systems can provide. But what if there was a way to get the same insights on the field with a fraction of the setup time and cost?

Dr. Josh Weinhandl, Associate Professor of Biomechanics at the University of Tennessee, is investigating which established Vicon metrics he collects in the lab correlate with more novel metrics teams are starting to measure outside of the lab with IMU sensors (inertial measurement units). There are a number of metrics, such as tibial anterior shear force, which have been used within the research. These are used as a surrogate for ACL loading. Therefore if there were correlations to that from data collected in the field, things may get very exciting for the researcher and the practitioner.

“If we can identify metrics that we can get from the IMU sensors that correlate well with these lab based measures that have already been identified as risk factors for ACL and other knee injuries, then we have a means to go out into the field and using IMU’s, gain comparable information.”

Lab and field data correlations

Josh has been collecting raw data with IMeasureU’s new blue trident sensor for a project looking at how data in the lab compares to data in the field. “We’ve been collecting a lot of raw data in conjunction with our Vicon system and looking for correlations,” Josh explains. “In the lab we are looking at ground reaction force measures, knee joint torques, and joint reaction forces. We are then analyzing them alongside those metrics that we can collect in the field such as peak acceleration and some of the gyroscope measures.”

“There was one athlete in particular who was highly asymmetrical to the left with a low number of high intensity impacts. They were clearly avoiding using that side and favoring the right but we didn’t know why.”

Identifying those at risk

“If we can identify metrics obtained from the IMU sensors that correlate well with these lab based measures that have already been identified as risk factors for ACL and other knee injuries, then we have a means to go out into the field and using IMU’s, gain comparable information,” Josh explains. “Performing tasks while the athletes wear IMU sensors may allow us to identify those who are at risk of traumatic injuries.”

There are a number of protocols which Josh uses when assessing athletes for ACL injury risk. However, replicating what is performed in the lab environment out in the field was paramount.

Lab based screening

“Our protocol in the lab often starts off with strength testing on the Biodex, examining quadriceps to hamstring strength ratios and right to left strength ratios in both quads and hamstrings. Then with our Vicon motion capture system the athlete performs some sport related tasks. That may be an overground run and cut, a stop jump or some type of landing task. We also often try to include an anticipation component into the task. During the task, the athlete is presented with a visual stimulus which signals a change of direction the athlete must react to.”

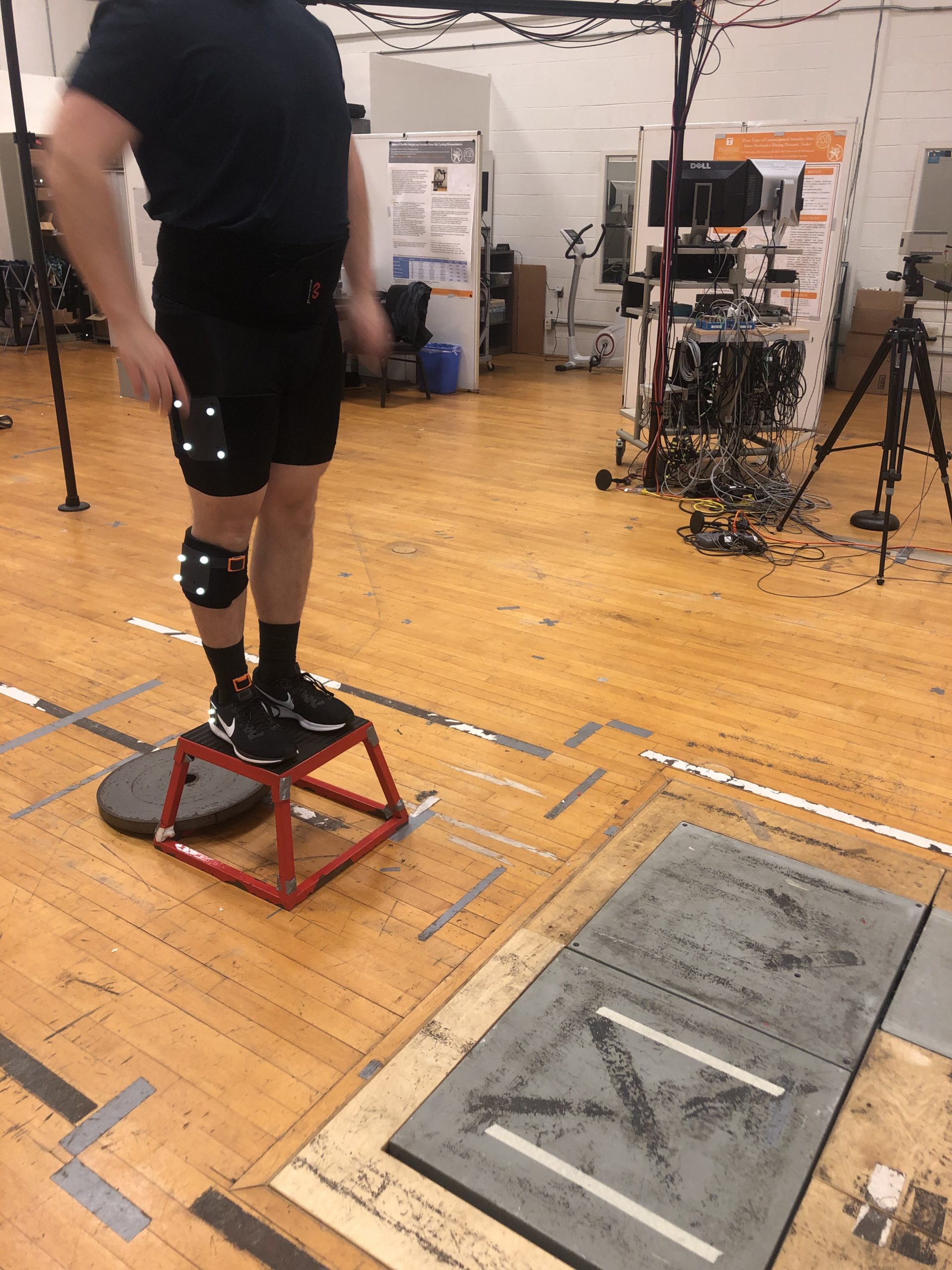

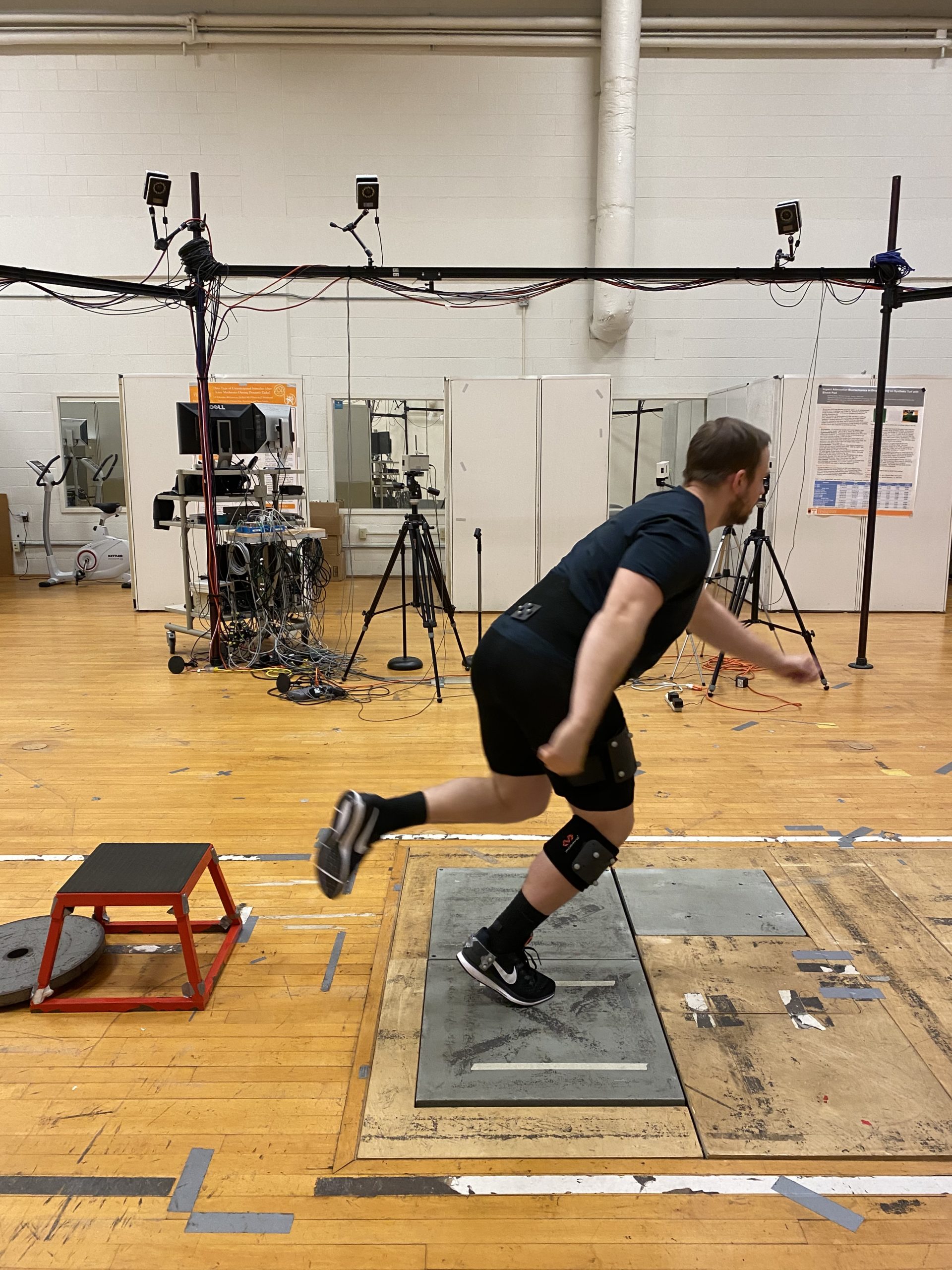

Drop jumps were the main movement Josh used to try to understand the correlation between the lab measures and data collected by the IMU sensors.

The study

“For this study, we place a 30cm box half the athletes height away from the target landing zone. The athletes will jump forward from the box to the target landing area. Upon landing on the ground they perform a vertical jump as fast and explosive as possible. Therefore, there is a forward anterior component to it, a rapid deceleration when making contact with the ground, and a secondary movement. This was undertaken with 18-25 year old collegiate populations but we are working to replicate this with younger athletes also.”

Although still early in the data analysis phase, Josh and his colleagues have seen some very exciting preliminary results.

“We are early in data analysis, however, our preliminary analysis shows that when we place IMUs at the distal tibia or at the tibial tuberosity, there is a correlation between resultant acceleration and anterior shear force at the knee.”

Showing the value of asymmetry data from IMU sensors

Not only has Josh been exporting the raw data for his research study, he and his colleagues have also been working with a group of division two female soccer athletes and collecting change of direction data using IMU Step.

“With the soccer players we’ve been focusing on the percentage of impacts that are high intensity and calculating asymmetry index. This data has been collected during agility drills which are common in strength and conditioning; a zigzag test, t-drill and a reactive agility test (RAT),” Josh explains. “We chose to look at asymmetry rather than bone stimulus. We did this because of the short duration of the task.”

“In looking at those asymmetry indexes and number of high impacts, we were able to categorize athletes into four boxes:

- Asymmetrical to the right with an increased number of high intensity impacts

- Asymmetrical to the left with an increased number of high intensity impacts

- Asymmetrical to the right with a low number of high intensity impacts

- Asymmetrical to the left with a low number of high intensity impacts.

Identifying those with an injury history

“We have now begun to rank the athletes and identify thresholds in two areas. One group that might indicate individuals who are overloading and another group that are actually under loading or avoiding impacts on a particular leg” Josh said.

This data is informing the future direction of their research and they are drawing exciting conclusions from the results.

“The preliminary comb through the data was pretty revealing. By simply splitting athletes into quartiles we were able to easily highlight those who were returning from injury.” Josh explains. “There was one athlete in particular who was highly asymmetrical to the left with low numbers of high impacts. They clearly avoided left impacts and favoring the right but we didn’t know why. Without prior injury history we couldn’t determine the cause of this asymmetry. We thought it might be a fear of reinjury or an undiagnosed injury. However when we spoke to the coaches they said that it made complete sense. This particular athlete did suffer an ACL injury but was clear to return.”

“If a coaching cue was ‘push the ground away’ during a jump, IMU sensors could provide instantaneous feedback to show the athlete how that differs to when he or she wasn’t actively thinking about that cue. This could also give coaches really interesting information regarding which cues may work best in various situations.”

Providing value with IMU sensors

Data of this kind backs up a coaches eye and intuition, however it can also give clarity and confidence that the process the coach undertakes is the right one. There is also much more to develop within this area of wearable technology.

“I believe that IMU sensors could provide real value to coaches. One area is giving objective data based on different coaching cues,” Josh continues. “For example, IMUs could provide instantaneous feedback to show the athlete after receiving a particular cue. This could also give coaches interesting information regarding which cues may work best in various situations”. This becomes possible with IMU systems like IMU Step, which offers live data capabilities. They allow practitioners to make on the stop decisions based on objective and reliable metrics.

The gold standard when assessing movement for any goal is optical, lab based motion analysis. However, its exceedingly difficult to get athletes at any level to the lab to conduct these kinds of assessments. IMU sensors bridge the gap and allow practitioners to take valid and reliable assessments specific in the field.

To explore how you can use IMU sensors to track your athletes in the field, get in touch with us to speak with a sports scientist.

Learn more

This case study builds on concepts we’ve explored in-depth at IMeasureU. Follow the links below to learn more –

IMU Step: Helping to monitor chaos during rehab?

How to Improve Patient Outcomes with Objective Data

Using inertial sensors to improve the return to play process: A case study with Loughborough University

Have an injured athlete? Get in touch with us and ask about a free trial of IMU Step to see how we can help your return to play.