The game of cricket often gets a bad rap for how hard it is on the athletes. As practitioners conduct more research into cricket matchplay with microsensors, we are coming to understand just how much stress the sport demands. Cricket’s high-intensity actions, particularly in fast bowlers, put the athletes at a higher risk of severe injury. Stress fractures are unfortunately injuries that every physio working in cricket deals with season after season.

Jamie Thorpe, Head of Science & Medicine/Lead Physiotherapist at Somerset County Cricket Club is no stranger to seeing the devastating effect a stress fracture can have on a player’s season. And it was because of this that after seeing an IMU Step data presentation at the 6th World Congress in Science and Medicine in Cricket, Jamie decided to investigate how inertial sensor data could help him understand the mechanisms behind these injuries.

“Because of the objective data from IMU Step we have been getting a deeper understanding of how he (the player) moves. This has allowed us to modify his bowling volume.”

Lumbar stress fractures in cricket

“We saw one presentation at the World Congress that really sparked my attention around bone stress injuries. Cricket, traditionally, has a lot of these types of injuries. Therefore we thought it would be interesting to see the technology in use in our environment. The lumbar spine stress fracture, although its prevalence among teams is low, can be a big-time loss injury. Although it is quite a small fracture, because of its location it can take up to six or seven months for a player to return to his optimum capabilities. And it can be a strange injury. Some athletes can have stress fractures with no symptoms, others can experience significant symptoms, with bone stress and no diagnosed fracture. This is where I thought IMU Step could give us insight.”

Although Somerset does have access to a GPS system to measure external load, Jamie was interested in looking at true biomechanical load. Initially, they were focusing on their fast bowlers but very quickly realized that their sensors had other applications.

“We have GPS units and we monitor run-up speed and distances covered. However, we often see ‘load’ as how many high-speed meters we have covered which I don’t think paints the whole picture. I wanted to look at load as an expression of force through the floor. If we were able to assign a number of Gs to a certain action, a bowler who is bowling a ball, for instance, we could make better decisions on return-to-play criteria, off-season training, training in different environments, etc. The interesting and useful information we could collect would be endless.”

The current COVID-19 situation is affecting everyone in professional sport. Somerset had planned to travel to Abu Dhabi prior to starting the season. And it was during this trip that IMU Step was going to be used to do a number of comparisons.

“Having IMU Step made us look a lot closer at every bit of the player’s day and how it impacts the total. We have previously looked at this as ‘time on feet’ but it just doesn’t tell us enough.”

Surface differences when bowling

“Our team was planning to use the sensors in Abu Dhabi during competition but unfortunately because of this current situation, we weren’t able to. We had some good baseline data of what training looked like here in the UK. We had seen some stark differences in intensity between guys bowling ‘looseners’ or going through drills vs when they were bowling at a batsman. That’s not overly surprising. However, it was the start of us building a picture of how our players prepare for competition. The next step for us was to compare how conditions and surface affected the amount of force bowlers were generating.”

If Jamie and the rest of the Sports Science and medicine/performance coaches at Somerset were going to gain a real impact on injury occurrence, they would need to understand whether they could offset or manage the forces that the fast bowlers were exposed to.

“During our off-season and pre-season, because of the weather in the UK, a lot of our work is done indoors. However, we have only our intuition and experience to try to understand how that work differs from that done outside. We were hoping to use our trip to Abu Dhabi to gain additional insight into this question. This could have positively impacted our future planning of pre-season and offseason work. We had started to look at both Bone Stimulus and Impact Load together. Our bone stress number tended to be around 250 for a pretty hard bowling session. But when we were doing a running session, it was coming up around the same, 250.”

“Obviously, when you look closer you can see that the bowling is producing some very very high intensities, coupled with very low periods in between. In contrast, the running is relatively low intensity but constant. We often don’t see the accumulation of the stress as we look at each individual component of the day as an individual entity.”

Understanding each individual component of the day, especially in a rehabilitation environment was key for Jamie. We generally consider fielding, for example, as a low-intensity activity. However, no one has officially quantified these types of sessions.

Understanding each component of the game

“Having IMU Step made us look a lot closer at every bit of the players’ day and how it impacts the total. We have previously looked at this as ‘time on feet’ but it just doesn’t tell us enough. For rehabbing players, we discussed putting the sensors on them from the start of the day to the end of the day to get a full picture. Having objective data from the sensors gives us the hard facts, no matter how difficult that may be to take.”

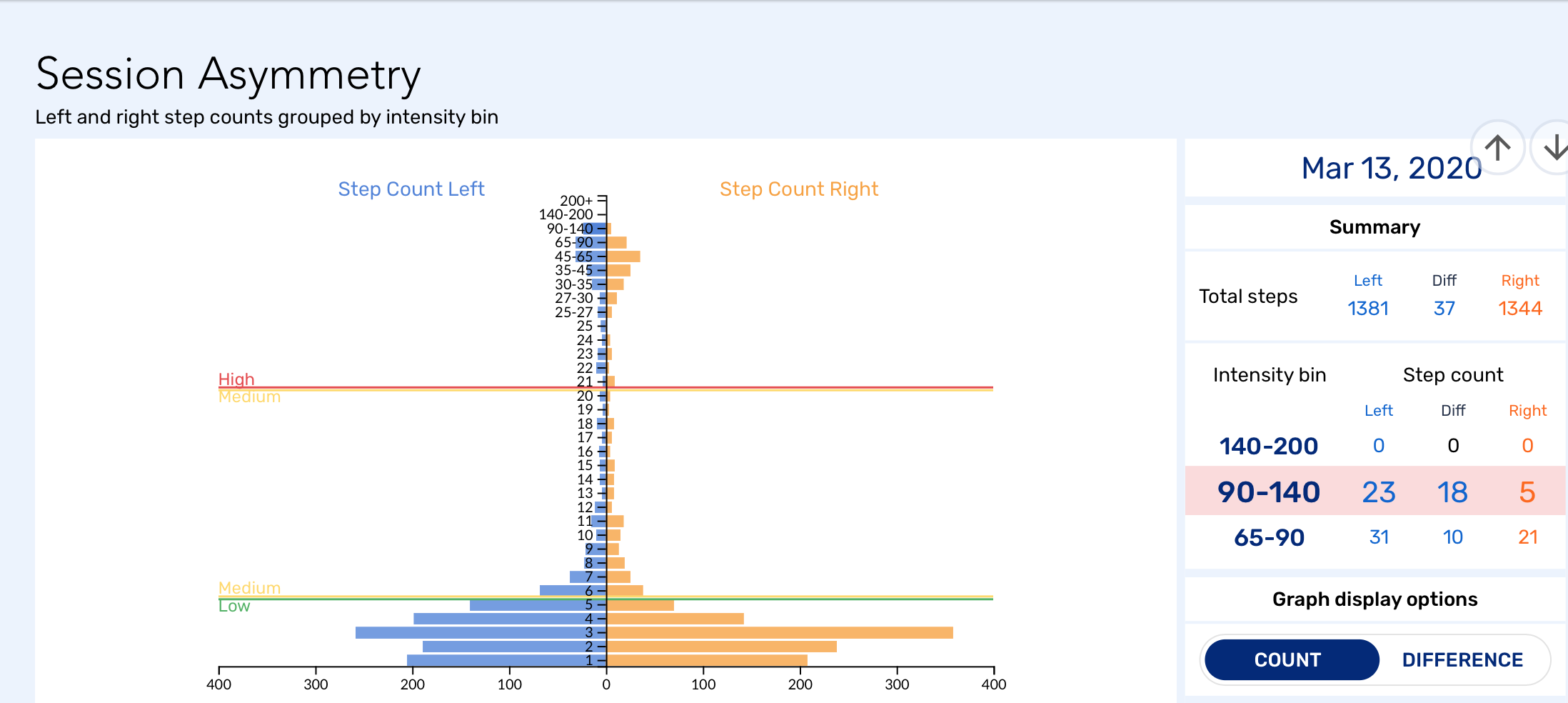

As they got familiar with IMU Step, the medical team were keen to dive into the detail with their bowlers. This led them to take a closer look at the asymmetry data.

“When we look and talk about fast bowlers, we often focus on the front foot which is the one that plants on the floor directly before the bowler releases the ball. That front leg can take up to 10 or 11 times body weight through it on each delivery. We saw that the Gs shot through the roof when performing a bowl in real time.”

“However, something very interesting was that the Gs also shot through the roof on the non-plant leg during the subsequent step after the ball is released. And in actual fact, it was pretty even. Maybe a bigger concern is that we focus so much on the initial plant and forget about the step afterward. This is also generating lots of force to then slow the bowler down. We found that this was actually more pronounced during white ball cricket vs red ball cricket. We thought this may be because if you are expecting the ball to come back at you sharply, you’re going to try to decelerate a lot harder to get ready for that.”

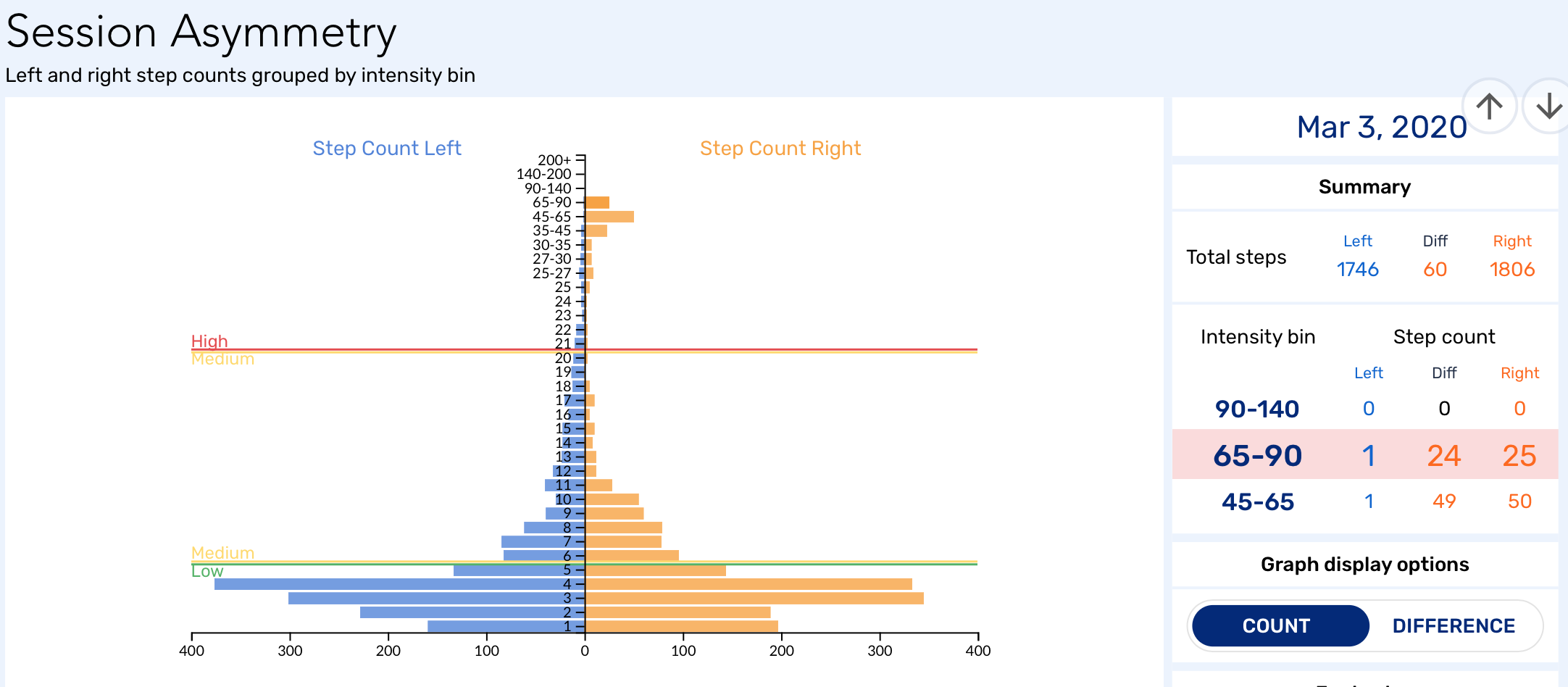

There is a higher prevalence of lumbar stress fractures in young fast bowlers, so Jamie chose one to track. This bowler was a medium-pace bowler who had suffered from several lumbar stress fractures in the past.

“Some athletes can have stress fractures with no symptoms, others have symptoms with no stress fracture. This is where I thought IMU Step could give us insight.”

Identifying loads through various bowling phases

“As a general rule, lumbar stress fractures are less likely to occur in spinners or medium pace bowlers. This is due to the reduced forces on their body. But when we put the sensors on this player we found he was putting more force through his front leg than some of our guys bowling at 90mph. We spoke to our bowling coaches and analyzed his run-up technique. We concluded that he was generating a lot more vertical force through the floor versus other horizontally oriented bowlers. However, historically he has been used for longer spells of bowling. This was due to his skill application and the control he brings with the ball. This, coupled with this data provides a possible insight into his injury history. Because of the objective data we got from IMU Step we got a deeper understanding of how he moves. This has allowed us to modify his bowling volume.”

Learn more

This case study builds on concepts that we’ve explored in-depth at IMeasureU. Follow the links below to learn more –

IMU Step: Helping to monitor chaos during rehab?

How to Improve Patient Outcomes with Objective Data

Using inertial sensors to improve the return-to-play process: A case study with Loughborough University

Have an injured athlete? Get in touch with us and ask about a free trial of IMU Step to see how we can help your return to play.